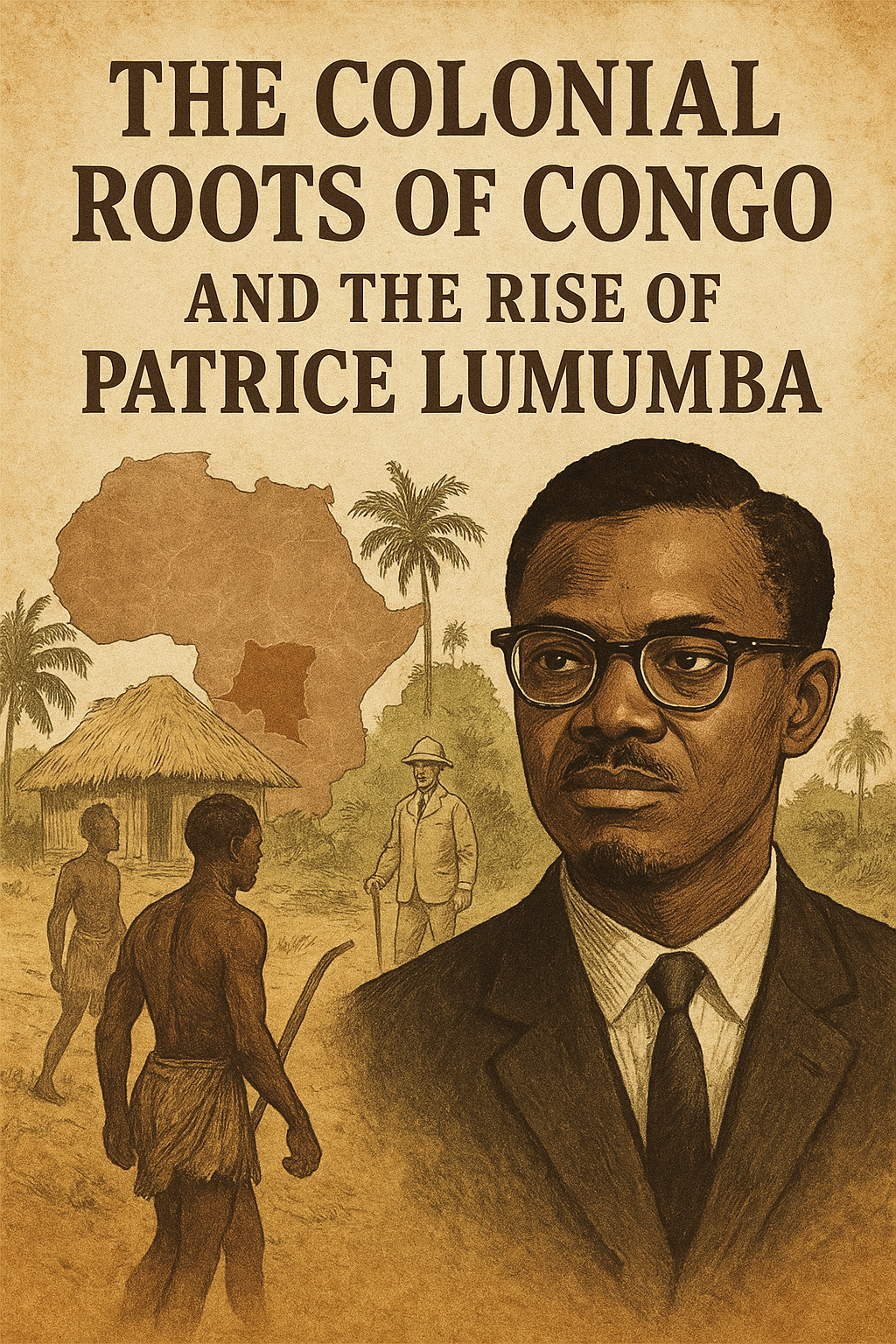

Part 1: The Colonial Roots of Congo and the Rise of Patrice Lumumba

When discussing the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), it is essential first to distinguish it from its neighbor, the Republic of Congo. Although they share a name and a river, their colonial histories diverged—one under France, the other under Belgium. The Democratic Republic of Congo, formerly the Belgian Congo, endured some of the harshest experiences of European imperialism. Into this world, in July 1925, Patrice Émery Lumumba was born. His short but dramatic life would transform him into one of Africa’s most important independence leaders.

Congo Before Lumumba: The Vision of Leopold II

The roots of Belgian involvement in the Congo can be traced to King Leopold II of Belgium, who reigned between 1865 and 1909. Unlike larger colonial powers such as Britain or France, Belgium at the time was a small European state with limited international influence. Yet Leopold nurtured grand ambitions. He dreamed of elevating his kingdom by acquiring overseas colonies, and Africa presented the perfect stage for his vision.

Leopold’s ambitions gained direction through the work of Henry Morton Stanley, a British-American explorer. Stanley became famous in 1871 for his dramatic meeting with the Scottish missionary David Livingstone, whom he reportedly greeted with the now-legendary phrase, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” After Livingstone’s death in 1873, Stanley continued his explorations, mapping out the central African landscape with detailed notes, charts, and reports.

These explorations revealed more than geography. Stanley highlighted the enormous natural wealth of the region: ivory, rubber, gold, and other valuable resources. His discoveries fired Leopold’s imagination. Where other European leaders hesitated, distracted by their own colonial pursuits, Leopold saw an opportunity. He realized that with the right strategy, Belgium could secure vast territories in Africa and join the ranks of Europe’s great colonial powers.

The Deceptive Treaties

Leopold recruited Stanley to help him establish a foothold in Central Africa. Armed with funds and authority from the king, Stanley returned to the Congo and began setting up trading posts and negotiating with local chiefs. But these agreements were deeply deceptive. The Congolese leaders often believed they were entering into simple friendship or trade arrangements, exchanging signatures for gifts such as cloth, tools, or alcohol. In reality, the documents ceded entire territories and populations to Leopold’s control.

By 1884, Leopold had consolidated these fraudulent contracts into a claim of sovereignty. His vision was formally endorsed at the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, a gathering of European and American powers organized by German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. The Berlin Conference aimed to manage the growing competition for Africa and avoid open conflict among colonial powers. It was here that Leopold’s personal rule over the Congo was recognized internationally, creating the so-called Congo Free State.

The Congo Free State: A Land of Atrocities

Despite its name, the Congo Free State was anything but free. It became Leopold’s private property, ruled not as a colony of Belgium but as his personal fiefdom. Leopold never set foot in the territory, yet he oversaw a regime of extraction and terror that shocked the world.

Rubber was the most lucrative commodity, in high demand due to the spread of bicycles, automobiles, and industrial machinery in Europe. Villages were forced to meet impossible rubber quotas. Failure was punished brutally—men were killed, women and children were taken hostage, and severed hands became grim tokens of compliance. Entire communities were uprooted, and the population declined catastrophically due to murder, starvation, disease, and displacement.

Reports of these atrocities began to leak out, thanks to missionaries, travelers, and whistleblowers such as E.D. Morel and Roger Casement. International outrage eventually pressured the Belgian Parliament to strip Leopold of personal control. In 1908, the Congo Free State was transferred from Leopold’s ownership to the Belgian state, becoming the Belgian Congo. Although some reforms followed, exploitation and racial inequality remained deeply entrenched.

Patrice Lumumba’s Early Years

It was into this environment of colonial inequality that Patrice Lumumba was born in 1925, in Onalua, a village in the Kasai region. His family lived far from the political and economic centers of colonial administration, but the weight of Belgium’s policies was felt everywhere. Congolese children, including Lumumba, were exposed to an education system designed not to cultivate leaders but to produce obedient workers.

At the age of eleven, Lumumba enrolled in a Catholic mission school. These schools emphasized discipline over intellectual freedom, and Africans were trained for manual labor rather than academic pursuits. Yet Lumumba stood out. He showed insatiable curiosity and a sharp intellect, qualities that even his teachers—despite the colonial biases of the system—could not ignore. Recognizing his hunger for knowledge, some lent him books, which he read late into the night by dim light, as his family was too poor to afford candles.

From an early age, Lumumba was outspoken. He challenged authority when he saw injustice and displayed a confidence that would later define his political career. Unlike many of his peers who accepted the colonial status quo, Lumumba believed in the dignity and potential of Africans. He refused to be boxed into the limited roles the Belgian system prescribed for Congolese youth.

The Weight of Memory

While Lumumba grew up decades after Leopold’s personal rule ended, the collective memory of that brutal era lingered. Stories of mutilations, massacres, and forced labor were passed down through families and communities. The Congo’s landscape itself bore scars of violence and exploitation. For many Congolese, including Lumumba, colonialism was not just a distant structure but a lived reality of oppression, poverty, and humiliation.

This history shaped Lumumba’s worldview. He was not simply an ambitious young man seeking power. He carried within him the frustration and aspirations of a people who had endured unspeakable suffering under foreign domination. His eloquence and defiance would later make him both a hero to his people and a threat to those invested in maintaining colonial privileges.

Part 2: Lumumba’s Path to Politics and the Struggle for Independence

A New Generation in a Colonial World

By the 1940s and 1950s, Congo was still firmly under Belgian control, but winds of change were sweeping across Africa. World War II had weakened European empires, and independence movements were gaining strength in places like Ghana, Kenya, and Algeria. The Congolese population—long excluded from meaningful participation in politics or administration—was beginning to stir.

Belgium had no real plan for Congo’s future. Unlike Britain and France, which had at least started experimenting with gradual political reforms in their colonies, Belgium clung to the idea that Congo would remain a dependency indefinitely. Belgian officials referred to Congolese as évolués (“evolved”) if they had received some education or adapted to European lifestyles. Yet even those given this label were treated as second-class citizens, with few rights and constant reminders of their “inferior” status.

It was in this atmosphere that Patrice Lumumba began to emerge as a voice of resistance.

Early Work and Exposure to the World

As a teenager, Lumumba had to abandon his formal education due to financial constraints. He took jobs in mining towns like Kindu and Kalima, where he experienced firsthand the harsh conditions endured by Congolese laborers. He later found employment with the colonial post office in Stanleyville (today’s Kisangani).

This job was pivotal. It gave him exposure to newspapers, books, and correspondence from around the world. Lumumba became an avid reader, consuming literature, political theory, and history. He studied the works of Enlightenment thinkers, African nationalists, and European philosophers. Unlike many Congolese of his generation, Lumumba developed a broad worldview that fused local realities with global currents.

At the same time, his eloquence and charisma were becoming apparent. Colleagues remembered him as someone who spoke passionately, argued fearlessly, and carried himself with unusual confidence. Even before entering formal politics, Lumumba was known in Stanleyville as a man who would not tolerate injustice.

The Turning Point: Political Awakening

By the early 1950s, Lumumba had joined associations of évolués, which were spaces where educated Congolese gathered to discuss ideas, culture, and limited political issues. While many of these groups focused on social activities, Lumumba pushed them toward political engagement. He wrote articles, gave speeches, and challenged colonial attitudes.

In 1956, a major political moment arrived. A group of Belgian professors issued a document known as the Thirty-Year Plan, which proposed a gradual path to Congolese independence over three decades. For many Congolese, this was insulting—it assumed Africans were incapable of self-government for another generation. Lumumba became one of the most vocal critics of this plan. He insisted that Congolese people were ready to govern themselves and that any delay was merely a tactic to preserve Belgian control.

Arrest and Radicalization

In 1955, Lumumba was arrested on charges of embezzlement from the post office. He spent over a year in prison. While the charges were controversial, the experience hardened him. Prison gave him time to reflect, read, and refine his political vision. Far from silencing him, incarceration elevated his reputation among Congolese who saw him as a victim of colonial repression.

Upon his release in 1957, Lumumba threw himself fully into politics. He joined the Mouvement National Congolais (MNC), a party he helped shape into a national movement. Unlike many Congolese political groups that were rooted in ethnic or regional loyalties, the MNC emphasized unity across tribal and provincial lines. Lumumba believed that Congo’s strength lay in its diversity and that independence could only succeed if the nation avoided fragmentation.

Independence Fever

By the late 1950s, Belgium could no longer ignore the growing demands for independence. Protests erupted in major cities, sometimes met with brutal crackdowns. The turning point came in January 1959, when riots in Leopoldville (today Kinshasa) shook the colonial administration. Dozens of Congolese were killed, and hundreds were arrested. The violence convinced Belgium that it could not maintain its grip indefinitely.

In this heated environment, Lumumba’s star rose quickly. He traveled, gave speeches, and built networks with other African leaders. In December 1958, he attended the All-African Peoples’ Conference in Accra, Ghana, hosted by Kwame Nkrumah, the leader of newly independent Ghana. For Lumumba, the experience was transformative. He connected with figures from across the continent who were fighting colonialism, and he returned to Congo more determined than ever to push for immediate independence.

The Road to Brussels

In early 1960, Belgium reluctantly organized a roundtable conference in Brussels to discuss Congo’s future. To the surprise of many Europeans, Congolese leaders—including Lumumba—demanded rapid independence. Rather than the 30-year timetable proposed earlier, they insisted on full sovereignty within months.

Belgian officials, caught off guard, agreed. It was a startling concession, reflecting both their underestimation of Congolese determination and their desire to avoid escalating conflict. Independence was scheduled for June 30, 1960.

Lumumba’s role during this period was decisive. His MNC emerged as one of the strongest political parties, winning broad support across ethnic and regional lines in the May 1960 elections. Although no single party secured a majority, Lumumba’s coalition-building skills positioned him as a central figure in the new government.

Congo’s First Prime Minister

On June 24, 1960, Patrice Lumumba was appointed the first Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Joseph Kasa-Vubu, another independence leader, became the first President. The arrangement reflected a balance between political factions, but tensions simmered beneath the surface.

For Lumumba, the appointment was the culmination of years of struggle. At just 34 years old, he embodied the hopes of millions of Congolese who had endured generations of exploitation and humiliation. But his boldness, eloquence, and uncompromising stance also made him a target—both for Belgium, which still hoped to influence the Congo, and for Cold War powers like the United States and the Soviet Union, who saw Congo as a strategic prize.

A Nation on the Brink

As the independence day approached, the challenges facing Lumumba were immense. Congo was vast, resource-rich, and diverse, but it was deeply unprepared for self-rule. The Belgian administration had deliberately restricted education and training for Congolese. At independence, only a handful of Congolese had university degrees, and fewer than twenty were qualified to serve as senior administrators.

Yet for Lumumba and his supporters, independence was not about perfection. It was about dignity, freedom, and the right of Congolese people to control their own destiny. The months leading up to June 30, 1960, were filled with both celebration and anxiety—a moment of triumph that also carried the seeds of turmoil.

Part 3: Independence, Lumumba’s Speech, and the Crisis of the Congo

June 30, 1960: A Day of Triumph and Tension

Independence Day in Congo was celebrated with a mix of joy, anxiety, and uncertainty. On June 30, 1960, crowds filled the streets of Leopoldville, singing, drumming, and waving flags. For millions of Congolese, this was the first time they could truly claim ownership of their nation after generations of Belgian rule.

At the official ceremony, King Baudouin of Belgium gave a speech praising the legacy of his great-uncle, King Leopold II. Baudouin suggested that Congo owed its progress to Belgium’s “civilizing mission,” a statement that deeply offended many Congolese. For the Belgian delegation, the day was meant to be a controlled, orderly transfer of power—an event showcasing Belgium’s generosity rather than Congo’s struggle.

Then Patrice Lumumba stood up to speak.

Lumumba’s Historic Speech

Lumumba’s words that day were not part of the official program. Only President Joseph Kasa-Vubu and King Baudouin were scheduled to address the crowd. But Lumumba insisted on speaking, and what followed became one of the most powerful speeches in Africa’s decolonization history.

He rejected the paternalistic narrative offered by Baudouin. Instead, Lumumba spoke directly to his people, reminding them that independence was not a gift from Belgium but the result of their own suffering and sacrifice.

“We have known humiliating slavery,” he declared. “We have experienced ironies, insults, and blows we endured morning, noon, and night because we were Black. Who will ever forget that to a Black, ‘you’ was never said, but only contemptuous ‘thou’?”

He acknowledged the forced labor, the land seizures, the violence, and the systemic racism of colonial rule. And then he proclaimed that Congo’s independence marked the restoration of dignity to its people.

The speech electrified the crowd, who erupted in cheers and applause. But it shocked the Belgian delegation. Many Belgians, including King Baudouin, saw Lumumba’s words as a personal insult and a direct attack on Belgium. What for Congolese was a moment of liberation, for the former colonizers became a moment of embarrassment.

A Divided Leadership

From the very beginning, Congo’s independence was complicated by political divisions. President Joseph Kasa-Vubu and Prime Minister Lumumba represented different styles of leadership. Kasa-Vubu was cautious and conservative, seeking compromise. Lumumba was bold, fiery, and uncompromising, determined to confront colonial legacies head-on.

These differences created tension within the new government. To make matters worse, Belgium was not willing to release control easily. Belgian officers still commanded the Congolese army, and Belgian corporations maintained dominance over mining and economic sectors.

The Army Revolt

Barely a week after independence, chaos erupted. On July 5, 1960, soldiers of the Force Publique, Congo’s national army, mutinied against their white officers. The revolt began when General Émile Janssens, the Belgian commander, told Congolese soldiers that independence would change nothing in the army—that they would still be commanded by Belgians.

The soldiers rebelled, attacking European officers and civilians. Panic spread, and thousands of Belgian settlers fled the country. Belgian troops intervened, ostensibly to protect civilians, but in reality they deepened the crisis by undermining Congo’s sovereignty.

Lumumba responded swiftly. He Africanized the army, renaming it the Armée Nationale Congolaise (ANC) and promoting Congolese officers to leadership positions. Joseph-Désiré Mobutu (later known as Mobutu Sese Seko) was rapidly elevated, becoming chief of staff. While this move restored some order, it also placed enormous power in the hands of ambitious young officers.

Katanga’s Secession

As if the army crisis was not enough, the mineral-rich province of Katanga declared independence on July 11, 1960. Led by Moïse Tshombe, Katanga’s secession was openly supported by Belgian mining companies such as Union Minière du Haut-Katanga, which wanted to maintain control of Congo’s lucrative copper and uranium resources. Belgian military advisers also backed Tshombe, ensuring Katanga’s survival as a breakaway state.

Katanga’s secession was devastating for Lumumba’s government. The province provided a large share of Congo’s revenue, and its loss threatened national unity. Lumumba appealed to Belgium to stop supporting the secession, but his pleas were ignored.

Appeal to the United Nations

Facing the twin crises of army mutiny and secession, Lumumba turned to the United Nations (UN) for help. He requested military assistance to protect Congo’s territorial integrity and force Belgium to withdraw its troops. The UN, under Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld, agreed to send peacekeepers but refused to intervene directly in Katanga’s secession. The UN maintained that it could not take sides in Congo’s internal political disputes.

Lumumba grew increasingly frustrated. To him, Katanga’s secession was not an internal issue but a colonial plot backed by Belgium. When the UN refused to act decisively, Lumumba sought help elsewhere.

Cold War Shadows

This was 1960, the height of the Cold War. The United States and the Soviet Union were competing for influence across the world, and Africa had become an important arena in this rivalry. Lumumba, desperate to save Congo’s unity, turned to the Soviet Union for assistance.

The Soviets provided planes, trucks, and advisors to help transport Congolese troops. This alarmed Washington, which feared Congo might fall into the Soviet sphere of influence. The United States saw Congo not only as a strategic location in Africa but also as a critical source of uranium—the same uranium used in the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Thus, in the eyes of Western powers, Lumumba became a dangerous figure—not just a nationalist leader but potentially a communist ally.

Political Showdown

Tensions within Congo’s leadership reached a breaking point. President Kasa-Vubu, encouraged by Belgian and Western interests, dismissed Lumumba as prime minister in September 1960. Lumumba, refusing to accept the decision, announced that Kasa-Vubu no longer had authority. The government was in paralysis.

The army, under Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, seized the opportunity. With Western backing, Mobutu carried out a coup on September 14, 1960. He placed Lumumba under house arrest, cutting him off from his supporters.

Lumumba’s Defiance

Even in confinement, Lumumba’s charisma remained unbroken. He continued to rally support among ordinary Congolese, who saw him as the embodiment of independence. But his enemies were determined. Belgium, the United States, and local rivals feared his ability to mobilize the masses.

In late November, Lumumba attempted to escape his confinement and join supporters in Stanleyville. He was captured by Mobutu’s forces, beaten, and humiliated in public. Despite international appeals for his release, his fate was sealed.

A Nation in Turmoil

By the end of 1960, Congo was spiraling into chaos. The army mutiny, Katanga’s secession, and Cold War interference had shattered the optimism of independence. The very resources that made Congo rich—copper, uranium, diamonds—were also the reason why foreign powers were determined to control it.

For Lumumba, the struggle was no longer just about independence. It was about survival, both for himself and for the vision of a united, sovereign Congo.

Part 4: The Fall of Lumumba and the International Conspiracy

The Net Tightens

By late 1960, Patrice Lumumba’s government was no longer functioning. The dismissal by President Joseph Kasa-Vubu, the coup staged by Colonel Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, and the continuing Katanga secession left Congo fragmented and unstable. Lumumba, once the face of independence, was now isolated, watched by enemies both inside and outside the country.

Yet even in his weakened position, Lumumba remained a threat. His popularity among ordinary Congolese was unmatched. Whenever he appeared, crowds gathered. To Belgium, which wanted to protect its mining interests, and to the United States, which feared Soviet influence, Lumumba represented a danger that had to be neutralized.

Western Fear of Communism

In the Cold War climate, Lumumba’s appeal for Soviet assistance was decisive. Washington had already been watching events in Congo with unease. The U.S. State Department and CIA interpreted Lumumba’s outreach to Moscow as proof that he could align Congo with the communist bloc.

This fear was amplified by Congo’s resources. The Shinkolobwe mine in Katanga had produced the uranium used in the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. For American officials, the idea of Congo’s uranium falling under Soviet influence was unacceptable.

Declassified documents later revealed the extent of U.S. concern. CIA Director Allen Dulles described Lumumba as “a threat to the peace and security of the world.” President Dwight Eisenhower, according to some testimonies, even authorized plans for Lumumba’s assassination.

Belgium shared this fear, though for different reasons. Belgian companies stood to lose millions if Lumumba succeeded in nationalizing mines or reclaiming control of Katanga. Brussels quietly supported efforts to remove him, providing advisors, weapons, and encouragement to Congolese rivals.

House Arrest and Escape

After Mobutu’s coup in September 1960, Lumumba was placed under house arrest in his residence in Leopoldville. He was heavily guarded but not completely cut off. Supporters smuggled him news, and some army units still pledged loyalty to him.

In late November, Lumumba decided to escape. He hoped to travel to Stanleyville, where his allies, including Antoine Gizenga, were gathering forces. If he could reach them, he might establish a rival government and rally resistance against both Belgium and Mobutu.

On the night of November 27, Lumumba slipped out of Leopoldville with his wife, Pauline, and their child. At first, his convoy managed to evade patrols. But word spread quickly, and Mobutu’s soldiers gave chase. After days of pursuit, Lumumba was captured near the Sankuru River.

Humiliation in Captivity

Lumumba’s capture was staged as a public humiliation. Soldiers tied him up, paraded him through villages, and beat him in front of jeering crowds. Images of the once-proud prime minister, disheveled and battered, shocked the world. Yet for many Congolese, the sight deepened their anger against those who betrayed him.

International observers, including the United Nations, protested his treatment, but the Security Council remained divided. Western nations resisted stronger action, while the Soviet Union accused the UN of complicity. In the middle of this stalemate, Lumumba’s fate was sealed.

Transfer to Katanga

Mobutu’s government, under pressure from Belgium and fearful of further unrest, decided to transfer Lumumba to Katanga in January 1961. It was a calculated move. Katanga was under the control of Moïse Tshombe, who viewed Lumumba as his mortal enemy. Belgian officers, still advising Katanga’s secessionist forces, ensured that Lumumba would not survive long after arrival.

On January 17, 1961, Lumumba and two of his close associates—Maurice Mpolo and Joseph Okito—were flown to Katanga. They were beaten during the flight, and on arrival they were handed over to Katangese authorities. Belgian officials, including police officers and military advisors, were present at every step.

The Assassination

That evening, Lumumba and his companions were driven to a secluded area outside Élisabethville (now Lubumbashi). They were tied to trees, shot by a firing squad composed of Katangese soldiers, and buried in shallow graves.

But even in death, Lumumba continued to worry his enemies. Fearing that his burial site might become a shrine, Belgian officers returned days later, exhumed the bodies, and destroyed them with acid. Only fragments—such as Lumumba’s teeth—remained.

The operation was kept secret, but suspicions spread quickly. Within weeks, rumors of Lumumba’s murder circulated across Africa and beyond. When his death was finally confirmed, it sparked outrage worldwide.

Global Reactions

Across Africa, Lumumba’s assassination was seen as a blatant act of neo-colonial interference. In Ghana, President Kwame Nkrumah declared him a martyr of African freedom. Demonstrations erupted in cities from Cairo to Dar es Salaam, with protesters denouncing Belgium, the United States, and the United Nations for their roles in the tragedy.

In the Soviet Union, newspapers portrayed Lumumba as a victim of Western imperialism. The USSR even named a university in Moscow after him—the Patrice Lumumba Peoples’ Friendship University—designed to train students from developing nations.

In the West, officials denied direct involvement, though suspicions persisted. Belgium maintained silence for decades, only admitting its role in Lumumba’s death in 2002, after a parliamentary inquiry revealed that Belgian officials had been complicit. The CIA’s involvement remains debated, but documents show that assassination plots against Lumumba were seriously considered, even if Belgian agents ultimately carried them out.

Congo Without Lumumba

With Lumumba gone, Congo entered a period of turmoil. Antoine Gizenga tried to continue his legacy by setting up a rival government in Stanleyville, recognized by several African nations and the Soviet Union. But the central government in Leopoldville, backed by the West, eventually crushed the rebellion.

Mobutu, who had played a key role in Lumumba’s downfall, gradually consolidated power. By 1965, he seized full control in a coup, declaring himself president. For the next three decades, Mobutu Sese Seko ruled Congo (renamed Zaire) as a dictator, supported by Western powers despite widespread corruption and repression.

The Martyrdom of Lumumba

Though he ruled for only a few months, Lumumba’s legacy grew after his death. His eloquence, his insistence on dignity, and his refusal to compromise with colonial powers made him a symbol of African liberation. He became part of a larger story: the struggle of newly independent nations to assert sovereignty in a world dominated by Cold War rivalries and economic exploitation.

To this day, Lumumba is remembered not only as the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of Congo but also as a martyr whose vision for a united, independent Africa challenged the structures of empire.

Part 5: The Legacy of Patrice Lumumba

A Life Cut Short, A Symbol Born

Patrice Lumumba lived only thirty-five years and governed Congo for barely three months, yet his story reverberates across decades. His assassination in January 1961 ended his physical role in politics but transformed him into a symbol—of African dignity, anti-colonial resistance, and the costs of defying global powers. For many, Lumumba became more powerful in death than he ever was in life.

African Reverberations

Across Africa, Lumumba’s name became synonymous with the unfinished struggle for liberation. His uncompromising speech on Independence Day, which denounced the humiliation inflicted by Belgian colonialism, captured the anger and hope of a continent in transition. Leaders such as Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, and Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt saw in him a fellow traveler—young, visionary, and unafraid to challenge Western dominance.

In countries still under colonial rule in the 1960s, Lumumba’s fate was a cautionary tale. It revealed how fragile independence could be when external powers still controlled economic resources and manipulated political rivalries. Yet it also inspired movements to press harder, to claim sovereignty not just in law but in reality.

Global Cold War Symbolism

Lumumba’s death was also absorbed into the ideological battles of the Cold War. The Soviet Union elevated him as a martyr of imperialist aggression. In 1961, it established the Patrice Lumumba Peoples’ Friendship University in Moscow, a school intended to educate students from Africa, Asia, and Latin America who were fighting colonialism or striving for development. Murals, posters, and speeches in socialist countries celebrated him as a fallen hero who resisted Western exploitation.

In the West, however, Lumumba was often portrayed as reckless, radical, or even dangerous. American and Belgian officials depicted his outreach to the Soviet Union as evidence of communist leanings, despite the fact that his appeal for assistance came only after the United Nations refused to intervene in Katanga. This narrative allowed governments in Washington and Brussels to justify their hostility toward him while downplaying their own roles in his downfall.

In Congo: Memory and Erasure

Within Congo itself, Lumumba’s memory was complicated by politics. Mobutu Sese Seko, who seized power in 1965 and ruled for over three decades, owed his rise in part to Lumumba’s removal. While Mobutu could not erase Lumumba’s popularity, he tried to control it. He occasionally invoked Lumumba’s name as a nationalist figure but suppressed genuine Lumumbist movements that challenged his dictatorship.

For Lumumba’s family, the years after his death were marked by grief and silence. His widow, Pauline, and their children lived under pressure and surveillance. The circumstances of his murder were concealed, and the truth emerged only slowly through investigative journalism, declassified documents, and later official inquiries.

It was not until the early 21st century that Belgium formally acknowledged its role. In 2002, the Belgian Parliament issued an apology, admitting “moral responsibility” for Lumumba’s death. In 2022, more than sixty years after the assassination, Belgium returned one of Lumumba’s teeth—one of the few remains kept by a Belgian officer involved in the disposal of his body. The ceremony was a deeply emotional moment for his family and for Congolese citizens who had waited decades for symbolic justice.

The Struggles of Postcolonial Congo

Lumumba’s death did not end Congo’s troubles; in many ways, it marked the beginning of deeper turmoil. The young nation descended into years of instability, with rebellions, foreign interventions, and economic chaos. Katanga’s secession was eventually crushed, but the struggle left scars. The United Nations’ intervention—one of the largest peacekeeping operations of its time—highlighted the difficulty of balancing sovereignty with international politics.

Under Mobutu, renamed Zaire, the country became a Cold War client state. Western governments supported him as a bulwark against communism, despite his authoritarianism and corruption. Billions of dollars of aid flowed into his regime, much of it stolen or squandered. The promise of independence that Lumumba had so passionately declared was replaced by dictatorship and decay.

Even after Mobutu’s fall in 1997, Congo continued to suffer. Civil wars, foreign interventions, and conflicts over minerals turned the nation into a battleground for regional powers and global corporations. For many Congolese, Lumumba’s dream of a sovereign, united, and dignified Congo still feels unfulfilled.

Lumumba as a Pan-African Visionary

Beyond Congo, Lumumba remains a central figure in Pan-African thought. He embodied the idea that African nations could not simply replace European rulers with local elites while leaving colonial structures intact. Independence, in his view, required true control over resources, unity across ethnic and regional lines, and the courage to stand up to external interference.

His writings and speeches are still studied in African universities. His emphasis on national unity has been cited in debates over federalism, ethnic conflict, and resource distribution. For activists fighting corruption, neo-colonial exploitation, or foreign interference, Lumumba’s life continues to provide a powerful example.

Cultural Legacy

Artists, musicians, and filmmakers across the world have kept Lumumba’s memory alive. Congolese songs mourned his death; African poets celebrated his defiance. Internationally, his story has been told in films like Raoul Peck’s Lumumba (2000) and in countless documentaries and biographies. His image—youthful, intense, and resolute—has appeared on murals, posters, and stamps.

To young Africans, especially in the 1960s and 1970s, Lumumba symbolized the courage to speak truth to power. Even today, in a world where global inequalities persist, he is remembered as a voice that refused to be silenced.

What Lumumba Represents Today

Sixty years after his assassination, Lumumba’s story continues to raise profound questions. What does independence mean when foreign companies still dominate natural resources? How can African nations overcome ethnic divisions and external manipulation? What happens to leaders who challenge powerful global systems?

For many, Lumumba represents both the promise and the peril of radical honesty in politics. He refused to flatter Belgium at independence, and he refused to choose sides in the Cold War—insisting instead on Congo’s sovereignty. That defiance made him a target, but it also made him immortal in memory.

In 2011, the African Union declared the 50th anniversary of his death a continental day of remembrance. Streets, universities, and monuments across Africa bear his name. In Kinshasa, his towering statue faces the road to N’Djili International Airport, greeting travelers with the image of a man who gave his life for his country’s dignity.

Conclusion: The Dream That Endures

Patrice Lumumba’s life was brief, but his vision was vast. He imagined a Congo where resources benefited its people rather than foreign powers, a Congo united across ethnic lines, and a Congo that stood proudly among the nations of the world. He believed that independence was not a gift but a right, and he paid for that belief with his life.

Today, Congo remains a land of contradictions—rich in minerals but scarred by conflict, vast in potential yet struggling with governance. Lumumba’s words and example continue to inspire new generations who seek to finish the work he began. His legacy is not only Congolese or African but global: a reminder that dignity, sovereignty, and justice are worth the highest sacrifice.